英语 动画 教学 字母

Note: this essay may also be found on Design Observer.

注意:这篇文章也可以在 Design Observer 上找到 。

My first-grade reading tutor gave the best stickers. Puffy, smelly, sparkly — she even had a few that were fuzzy. At that age I was a tornado of excitement. The last thing I wanted to do was settle down and sound out words, but the promise of tiny trophies on my spelling notebook proved to be persuasive. I remember how it felt to run my finger over the fuzzy stickers, but I can’t remember how it felt to struggle with reading. As a father I see clearly now just how steep the climb to literacy can be. The frustrating illogicalities of English are enough to reduce any child into a puddle of doubt.

我的一年级阅读导师给了最好的贴纸。 浮肿,有臭味,闪闪发光-她甚至还有一些模糊的感觉。 在那个年龄,我是激动的龙卷风。 我想做的最后一件事是安定下来,说出话来,但我的拼写笔记本上的小奖杯的承诺被说服了。 我记得我的手指在模糊的贴纸上摸上去的感觉,但是我不记得在阅读上挣扎的感觉。 作为父亲,我现在清楚地看到扫盲的难度有多大。 英语令人沮丧的不合逻辑足以使任何孩子陷入疑惑。

Doubt is a prime example of why English can be so bewildering. The word isn’t spelled the way it sounds. Originally doubt was spelled dout. It was spelled this way because the word comes from the Old French word doute, and also because it just makes sense to spell it that way. Then sometime in the sixteenth century, around the birth of the dictionary, the powers that be decided they needed to imbue the common British tongue with the glow of ancient religious scripture. So they set about fabricating connections between English and Latin. The Old French word doute was inspired by the Latin word dubitum. And so a b was inserted into the English word doubt — phonology and emergent readers be damned. The dictionary is riddled with words that were separated from phonologically accurate spellings by the allure of Latin.

怀疑是为什么英语如此令人困惑的一个典型例子。 这个单词的发音方式不正确。 最初怀疑是被拼写DOUT。 之所以这样拼写,是因为该单词来自古法语单词doute ,并且因为以这种方式拼写才有意义。 然后在16世纪的某个时候,大约是字典的诞生时,被确定的力量需要它们才能使古老的宗教经文焕发英伦共同的语言。 因此,他们着手建立英语和拉丁语之间的联系。 古法语单词doute受到拉丁单词dubitum的启发。 因此,在英语单词“ 疑问”中插入了b-语音学和该死的新兴读者。 字典中充斥着一些单词,这些单词由于拉丁语的吸引力而与语音准确的拼写分开。

Some historians argue that other words were separated from phonologically accurate spellings in response to their letterforms. In medieval times Carolingian minuscule script was common and characterized by letters built from thick vertical strokes — also known as minims — with thin horizontal connectors. Picture a precursor to the blackletter masthead of The New York Times. Words with a critical mass of minims often proved illegible, especially if their delicate horizontal connectors faded. For example, without horizontal connections a word like minimum appears at a glance to be a series of 15 tightly spaced, but otherwise unrelated, vertical strokes. In response to this recurring legibility issue the letter u was replaced with the letter o in words with runs of minims like tun, which became ton. The letter c was also inserted before the letter k as a minim buffer in words like flik, which became flick.

一些历史学家认为,其他单词是根据语音形式与语音准确拼写分开的。 在中世纪,加洛林语的小写字母很常见,其特征是字母由粗笔直的笔触(也称为极小字)和细的水平连接器组成。 想象“纽约时报”发黑的标头的前身。 具有极小临界质量的单词通常被证明难以辨认,尤其是当其精致的水平连接器褪色时。 例如,在没有水平连接如最小的单词出现一目了然为一系列15紧密间隔的,但在其他方面不相关的,垂直笔划。 针对此反复出现的易读性问题,字母u被替换为字母o ,单词tun最小,如tun ,变成ton 。 字母c也在字母k之前插入,作为flik等单词的最小缓冲,从而变得轻弹 。

To be fair, it should be acknowledged that the English we write today resulted from the convergence of a plurality of histories, and the shape of letterforms did not have an equally weighted influence across all of them. Many medieval scribal practices existed contemporaneously. Specifically, it was the Anglo-Norman scribes who made a focused effort to resolve the effect of minim sequences. Still, even though letterform inspired spelling adjustments heralded from a single branch of the English evolutionary tree, they did survive into current use.

公平地讲,应该承认,我们今天撰写的英语是由多种历史的融合造成的,而字母的形状并没有在所有语言中具有同等的加权影响。 许多中世纪的抄写手法同时存在。 具体来说,正是盎格鲁·诺曼(Anglo-Norman)抄写员致力于解决最小序列的影响。 尽管如此,尽管从英语进化树的单个分支中预言了字母形式的启发性拼写调整,但它们确实可以保留到当前使用中。

Learning to read English is hard because it doesn’t make sense. At the heart of English’s nonsense is a persistent disconnect between its graphemes and phonemes. A grapheme is a letter, or a number of letters, that represents a sound in a word, and that sound is a phoneme. In his book Reading in the Brain cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene notes that “Reading difficulty varies across countries and cultures, and English has probably the most difficult of all alphabetic writing systems. Its spelling system is by far the most opaque — each individual letter can be pronounced in umpteen different ways, and exceptions abound. Comparisons carried out internationally prove that such irregularities have a major impact on learning. Italian children, after a few months of schooling, can read practically any word, because Italian spelling is almost perfectly regular. No dictation or spelling exercises for these fortunate children: once they know how to pronounce each grapheme, they can read and write any speech sound.”

学习阅读英语很困难,因为这没有意义。 英语废话的核心是其字素和音素之间的持续断开。 字素是一个字母或多个字母,代表一个单词中的声音,而该声音是一个音素。 认知神经科学家斯坦尼斯拉斯·德海恩(Stanislas Dehaene)在他的《 大脑中的阅读》一书中指出:“阅读困难因国家和文化而异,英语可能是所有字母书写系统中最困难的。 到目前为止,它的拼写系统是最不透明的-每个单独的字母可以以多种不同的方式发音,并且异常情况很多。 在国际上进行的比较证明,这种违规行为对学习有重大影响。 经过几个月的学习,意大利儿童几乎可以阅读任何单词,因为意大利语的拼写几乎是正常的。 这些幸运的孩子无需进行听写或拼写练习:一旦他们知道如何发音每个字素,他们就可以读写任何语音。”

In the United States teachers guide students across this landscape of gerrymandered spelling and illogical pronunciation with the help of various leveled reading systems. The most common systems, which are sometimes used in concert, are the Guided Reading Level system, The Lexile Framework, and the Grade Level Equivalent system. Books are assessed and labelled with alphabetic or numeric levels which describe their difficulty. A student’s growth is measured by assessing their reading ability and promoting them up the levels as their reading fluency and comprehension improve. For example, in the Guided Reading Level system students begin with books labeled “level A” in Kindergarten, and by 5th grade they’re reading “level Z.”

在美国,老师们借助各种水平的阅读系统,引导学生跨过杂乱无章的拼写和不合逻辑的发音。 有时经常一起使用的最常见的系统是“指导阅读水平”系统,“ Lexile框架”和“等效年级水平”系统。 评估书籍并用字母或数字级别描述书籍的难度。 通过评估学生的阅读能力并随着他们的阅读流利度和理解力的提高而提高他们的水平来衡量学生的成长。 例如,在“引导阅读水平”系统中,学生从幼儿园的标有“ A级”的书开始,到5年级时,他们正在阅读“ Z级”。

A book’s reading level is defined by many criteria. In the Guided Reading Level system criteria include:

一本书的阅读水平由许多标准定义。 在“指导阅读水平”系统中,标准包括:

Length: Lower levels feature a small number of words, lines per page, and pages per book. Higher levels feature longer, denser texts.

长度:较低的级别仅包含少量单词,每页行数和每本书页数。 较高的级别具有更长,更密集的文本。

Structure and organization: Lower levels feature simple, repetitive plots. Higher levels feature stories that require more interpretation.

结构和组织:较低级别具有简单的重复图。 较高级别的故事需要更多的解释。

Imagery: Lower levels feature pictures that portray the text literally to help students decode individual words. Higher levels feature less supportive pictures at a lower frequency.

图像:较低级别的图像以文字形式描绘文字,以帮助学生解码单个单词。 较高的级别以较低的频率提供较少支持的图像。

Words: Lower levels feature high-frequency words. Higher levels feature multisyllabic words and a broader vocabulary.

单词:较低级别具有高频单词。 较高的级别具有多音节单词和更广泛的词汇。

Phrases and sentences: Lower levels feature simple sentences. Higher levels feature longer, more complex sentences with embedded clauses.

短语和句子:较低级别具有简单的句子。 较高的级别具有包含子句的更长,更复杂的句子。

Literary features: Lower levels feature straightforward storytelling. Higher levels feature more complex devices such as flashbacks and metaphors.

文学功能:低级功能具有简单的讲故事功能。 较高的级别具有更复杂的设备,例如闪回和隐喻。

Content and theme: Lower levels feature topics and themes that are familiar to younger children. Higher levels feature sophisticated themes that require background knowledge for comprehension.

内容和主题:较低级别的功能包含年幼儿童熟悉的主题和主题。 较高的级别具有复杂的主题,需要了解背景知识。

Typography: Lower levels feature large point sizes with wide word and line spacing. Higher levels feature smaller point sizes with tighter word and line spacing.

印刷术:较低的水平具有较大的字号,字和行间距较宽。 较高的级别具有较小的点大小,字和行间距更紧密。

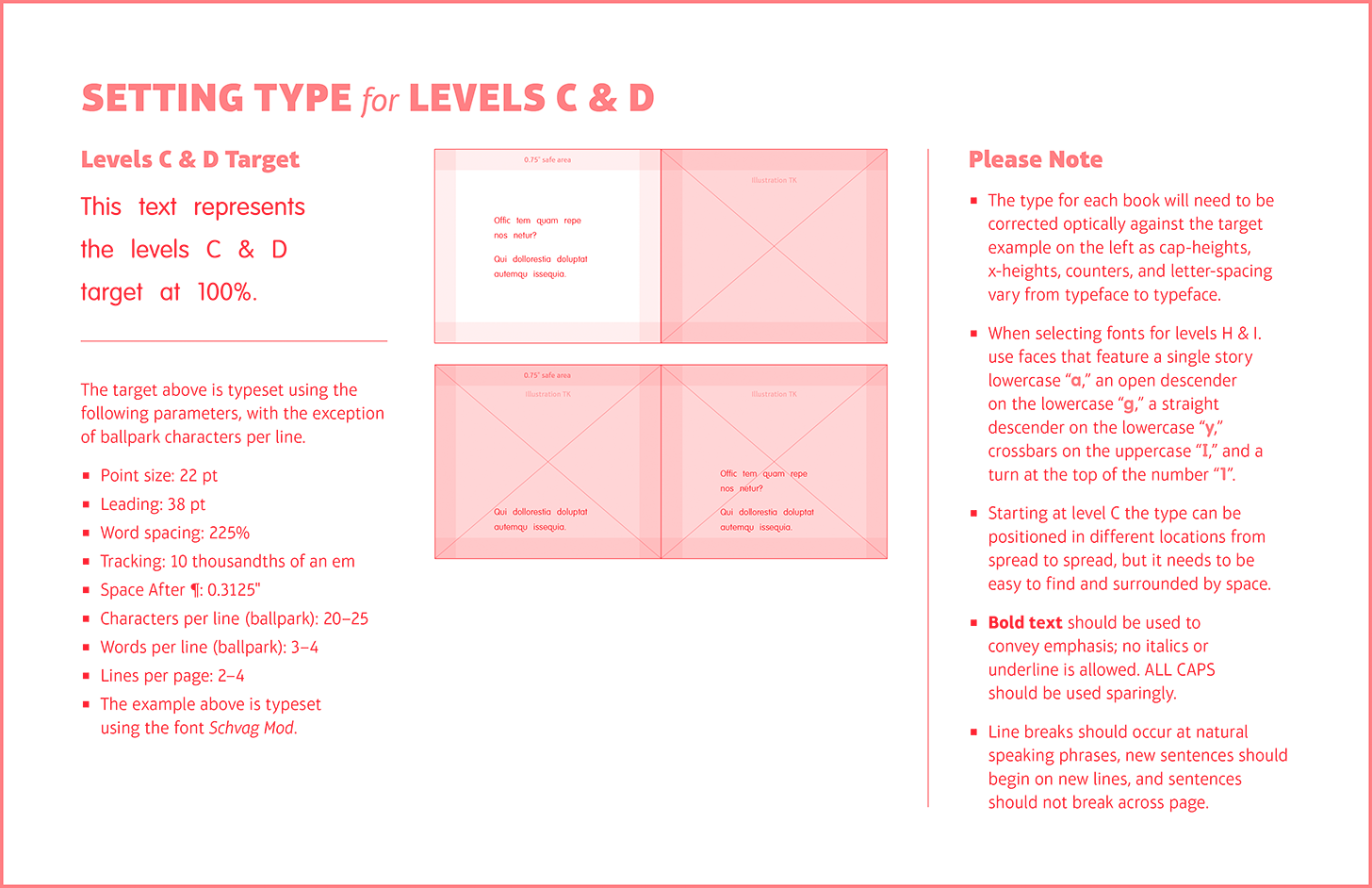

The Guided Reading Level system acknowledges that typographic properties — referred to in education circles as perceptual features — play an important role in a student’s reading fluency and comprehension, but guidelines for typesetting leveled text rarely go much deeper than the preceding paragraph. Professional levelers often describe making typographic judgment calls based on sensibilities honed from countless hours of experience with leveled texts. In this way the typographic principles of leveled reading are a textual feedback loop that can limit input from professional designers.

引导阅读水平系统承认,印刷属性(在教育界称为感知功能)在学生的阅读流利度和理解力方面起着重要作用,但是排版水平文本的准则很少比上一段更深入。 专业的水准测量人员通常会根据根据无数小时的水平水准文字磨练而产生的敏感性来描述进行印刷判断。 这样,水平阅读的印刷原理就是文本反馈循环,可能会限制专业设计师的输入。

Robust typesetting guidelines for leveled texts do exist, but primarily as internal support documents for design teams at educational publishers. These documents aren’t typically referenced by professional levelers, and it’s the levelers who define a book’s official reading level.

确实存在针对分级文本的健壮的排版指南,但主要是作为教育出版商的设计团队的内部支持文件。 这些文件通常不被专业的调平器所引用,而是由调平器来定义一本书的官方阅读水平。

In the past I’ve been charged with leading the design of proprietary typographic leveling guidelines. I can report from firsthand experience that developing such guidelines is far less straightforward than you might imagine. Each of the leveling criteria listed above interact with each other, and with the properties of each typeface and book, in complex ways.

过去,我一直负责领导专有的印刷水准仪设计指南。 我可以从第一手经验中报告,制定这样的指南远没有您想象的那么简单。 上面列出的每个校平标准都以复杂的方式相互影响,并且与每种字体和书本的属性相互作用。

For example, it’s difficult to prescribe a specific point size for a specific reading level in the abstract without also prescribing a specific typeface and book size. Typographic properties like x-height (the height of the lowercase letters) and book properties like trim size (the size and aspect ratio of the book) have a dramatic impact on how large text feels irrespective of its point size.

例如,在不指定特定字体和书本大小的情况下,很难为摘要中的特定阅读水平规定特定的磅数。 诸如x高度(小写字母的高度)之类的印刷属性以及诸如修剪尺寸(书籍的大小和纵横比)之类的书籍属性对大文本的感觉产生巨大影响,而不论其点号如何。

But mandating a specific typeface across a range of books intended for reading instruction runs counter to the belief within education circles that having a diverse range of authentic texts for students is critical to their growth as readers. “Authentic texts” refer to books that weren’t written specifically as tools for use in reading instruction, like the “See Spot run” basal readers that were popular throughout the mid-to-late 20th century. So even if an educational publisher develops a library of leveled picture books specifically for use as tools in reading instruction the books can’t feel that way. Every book must feel unique.

但是,在用于阅读指导的各种书籍中强制使用一种特定的字体,这与教育界的信念背道而驰,教育界认为,为学生提供多种多样的真实文本对于他们作为读者的成长至关重要。 “真实的文本”是指不是专门用作阅读教学工具的书籍,例如在整个20世纪中叶左右流行的“ See Spot run”基础读者。 因此,即使教育出版商开发了专门用于阅读指导的水平图画书库,这些书也不会有这种感觉。 每本书必须感觉独特。

My solution was to develop a typesetting target — a paragraph of sample text that designers were asked to use to optically correct the size and spacing of their body text. But even after developing a full alphabet of leveled reading typesetting targets that were vetted and approved by our editorial and leveling teams, we still ran into exceptions. For example, the gestalt of a tiny book, with a particular illustration style, reframed the typesetting target for that book’s level as too large in one particular case.

我的解决方案是开发一个排版目标-一段示例文本,要求设计师使用这些文本来光学校正其正文的大小和间距。 但是,即使在制定了由我们的编辑和水准团队审查和批准的完整的水准阅读排版目标字母表之后,我们仍然遇到了例外。 例如,一本具有特定插图风格的小书的格式像在某种情况下将该书的排版目标重新定为太大。

Building, and implementing, detailed typesetting guidelines for leveled texts is challenging, but the following research suggests that rising to this challenge produces measurable gains for young readers. Dr. Bonnie Shaver-Troup, an educational scholar, and Thomas Jockin, an educator and type designer, teamed up to develop a set of seven font families, collectively named Lexend, which were designed with the goal of improving reading fluency. Lexend’s variable width design rests on the foundational belief that “a font, much like the prescription in a pair of eyeglasses, should change based on the reader’s unique needs.”

构建和实施针对水平文本的详细排版指南具有挑战性,但是以下研究表明,应对这一挑战可为年轻读者带来可观的收益。 教育学者Bonnie Shaver-Troup博士与教育家兼字体设计师Thomas Jockin共同开发了七个字体家族,统称为Lexend,旨在提高阅读流畅度。 Lexend的可变宽度设计基于以下基本信念:“一种字体,就像一副眼镜中的处方一样,应根据读者的独特需求进行更改。”

In one study conducted by Dr. Shaver-Troup twenty-third graders were asked to read for one minute in five fonts — New Times Roman (the control), and then four of the Lexend Series: Regular, Deca, Mega, and Giga. The text was typeset at 16 points and was a couple of levels above the participants’ current grade level to “ensure the typography was being measured, rather than reading competency.” The students were asked to read aloud, and the number of correct words per minute was noted as an indication of fluency. Seventeen out of nineteen students had better fluency scores with Lexend than with New Times Roman. The use of Lexend resulted in a 19.8% instant fluency gain.

在Shaver-Troup博士进行的一项研究中,要求二十三年级的学生阅读五种字体一分钟-New Times Roman(对照),然后阅读Lexend系列中的四种:Regular,Deca,Mega和Giga。 文本的排版为16分,比参与者当前的年级水平高出几个级别,以“确保对字体进行了衡量,而不是阅读能力。” 要求学生大声朗读,并记录每分钟正确单词的数量,以指示其是否流利。 Lexend的19名学生中有17名的流利度得分高于New Times Roman。 Lexend的使用使即时流利性提高了19.8%。

The majority of reading performance studies that have explored the effects of manipulating a text’s font, point size, line length, letter-, word-, and line-spacing have examined the impact of these perceptual features on reading rate and accuracy. Less frequently examined is the impact on reading comprehension.

大多数阅读性能研究都探讨了操纵文本的字体,磅值,行长,字母,单词和行距的影响,这些研究都研究了这些感知特征对阅读率和准确性的影响。 较少检查的是对阅读理解的影响。

In a study conducted by Dr. Tami Katzir, Dr. Shirley Hershko, and Dr. Vered Halamish, forty-five fifth graders were asked to read four age-appropriate texts. The control text was typeset using the same typographic properties that are commonly used in fifth grade textbooks. The other three texts were intentionally designed to be more difficult to read, using combinations of smaller point sizes and tighter spacing. Their hypothesis was that making the text less comfortable to read would slow students down, and their slower reading speed would lead to higher comprehension scores.

在塔米·卡齐尔(Tami Katzir)博士,雪莉·赫什科(Shirley Hershko)博士和韦拉德·哈拉米什(Vered Halamish)博士进行的一项研究中,要求四十五名五年级学生阅读适合年龄的四篇课文。 使用与五年级教科书中常用的印刷属性相同的排版属性对控制文本进行排版。 其他三本书经有意设计为更难阅读,结合使用了较小的磅值和更紧密的间距。 他们的假设是,使课文阅读不舒适会降低学生的学习速度,而阅读速度较慢则会导致学生的理解力得分更高。

They found that using a smaller point size to achieve intentional disfluency produced an instant 10% gain in comprehension. Line length and spacing had less of an effect. They found this counterintuitive correlation between reading difficulty and improved comprehension was unique to older students and in fact found the inverse to be true with younger students.

他们发现,使用较小的磅数来实现有意的流落感可以使理解力立即提高10%。 线长和间距影响较小。 他们发现,阅读困难与理解能力之间的这种反直觉的关联是年长的学生所独有的,实际上,相反的关系在年轻的学生中是正确的。

The researchers summarized their observations succinctly: “The interaction between the reader and the text is not only content-based, nor does it solely relate to factors such as background knowledge, proficiency in decoding, spelling etc. In fact, text presentation changes the way information is encoded and processed. This notion has been previously suggested for the reading rate and accuracy of young children. In the current research we suggest that a similar effect exists for higher-level processing, i.e., reading comprehension.”

研究人员简洁地总结了他们的观察结果:“读者与文本之间的交互不仅基于内容,也不仅仅与诸如背景知识,解码能力,拼写等因素有关。事实上,文本表示会改变方式信息被编码和处理。 先前已经提出了关于幼儿的阅读率和准确性的概念。 在当前的研究中,我们建议在更高层次的处理中也存在类似的效果,即阅读理解。”

This concept of intentionally designing disfluent long-form reading experiences runs counter to many of the design and leveling community’s core principles. Designers and levelers are taught to prioritize readability above all. Dr. Katzir, Dr. Hershko, and Dr. Halamish’s research into “desirable difficulty” highlights the potential benefits of reviewing long-held typographic, and leveling, best practices through the lens of recent reading research.

故意设计不同的长篇阅读体验的这一概念与许多设计和水准社区的核心原则背道而驰。 教给设计师和矫平器首先要优先考虑可读性。 卡齐尔(Katzir)博士,赫什科(Hershko)博士和哈拉米什(Halamish)博士对“理想的困难”的研究突出了通过近期阅读研究的角度来回顾长期以来一直保持的印刷和水准最佳实践的潜在好处。

Reading is a verb that speaks to what happens in a person’s mind. In school we practice reading until the action becomes automatic enough for the letterforms to tumble down into our subconscious. Perhaps this is why typography is sometimes framed as an afterthought — a decorative element that sits at a distance from the real business of ideas. But reading and the ideas that reading inspires aren’t a byproduct of a text’s meaning alone. The ideas we come to as a result of reading are inextricably bound with the physical identity of a text.

阅读是一个动词,可以说出一个人的想法。 在学校里,我们练习阅读,直到动作变得足够自动以使字形下降到我们的潜意识中为止。 也许这就是为什么有时将版式设计为事后思考的原因-一种装饰元素,与真正的创意业务相距遥远。 但是,阅读和阅读启发的思想本身并不是文本含义的副产品。 阅读所产生的思想与文本的物理特性密不可分。

The leveling and design communities should further research the precise correlation between typography, fluency, and comprehension, with the goal of establishing more precise typographic recommendations for reading instruction. Doing so will produce instant fluency and comprehension gains for children who face the steep slope of English’s illogicality. Typography is a foothold that can help hoist children up over their doubts and onto the summit of their literate selves.

水平和设计社区应进一步研究排版,流利度和理解力之间的精确相关性,以期建立更精确的排版建议以阅读指导。 这样做将为面对英语不合逻辑的陡峭儿童提供即时的流利度和理解力。 字体印刷是一个立足点,可以帮助孩子克服疑惑,升入识字自我的顶峰。

Bridges, Lois Bridges 26 April 2018. “All Children Deserve Access to Authentic Text.” EDU, edublog.scholastic.com/post/all-children-deserve-access-authentic-text#.

路易斯·布里奇,布里奇,桥梁,2018年4月26日。“所有儿童都应获得真实的文本。” EDU edublog.scholastic.com/post/all-children-deserve-access-authentic-text#。

“Base Font Effect on Reading Performance.” Readability Matters, 1 Feb. 2020, readabilitymatters.org/articles/font-effect.

“基本字体对阅读性能的影响。” 可读性问题》 ,2020年2月1日, readabilitymatters.org / articles / font- effect。

“Change the Way the World Reads.” Lexend, www.lexend.com/.

“改变世界的读书方式。” Lexend , www.lexend.com /。

French, M. M. J., et al. “Changing Fonts in Education: How the Benefits Vary with Ability and Dyslexia.” The Journal of Educational Research, vol. 106, no. 4, 2013, pp. 301–304., doi:10.1080/00220671.2012.736430.

法语,MMJ等。 “改变教育中的字体:收益如何随能力和阅读障碍而变化。” 教育研究杂志 ,卷。 106号 2013年4月,第301-304页,doi:10.1080 / 00220671.2012.736430。

Katzir, Tami, et al. “The Effect of Font Size on Reading Comprehension on Second and Fifth Grade Children: Bigger Is Not Always Better.” PloS One, Public Library of Science, 19 Sept. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3777945/.

Katzir,Tami等。 “字体大小对二,五年级儿童阅读理解的影响:更大并不总是更好。” 公共科学图书馆PloS One ,2013年9月19日, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov / pmc / articles / PMC3777945 / 。

“The Old English Roots of Modern English Spelling.” The History of English Spelling, 2012, pp. 33–64., doi:10.1002/9781444342994.ch3.

“现代英语拼写的古老英语根源。” 《英语拼写史》 ,2012年,第33–64页,doi:10.1002 / 9781444342994.ch3。

“The Old English Roots of Modern English Spelling.” The History of English Spelling, 2012, pp. 33–64., doi:10.1002/9781444342994.ch3.

“现代英语拼写的古老英语根源。” 《英语拼写史》 ,2012年,第33–64页,doi:10.1002 / 9781444342994.ch3。

Pondiscio, Robert, and Kevin Mahnken. “Leveled Reading: The Making of a Literacy Myth.” The Thomas B. Fordham Institute, fordhaminstitute.org/national/commentary/leveled-reading-making-literacy-myth.

庞迪西奥,罗伯特和凯文·马肯。 “水平阅读:识字神话的形成。” 托马斯·B·福特汉姆研究所 (fordhaminstitute.org)/ national / commentary / leveled-reading-making-literacy-myth。

Reber, Rolf, et al. “Effects of Perceptual Fluency on Affective Judgments.” Psychological Science, vol. 9, no. 1, 1998, pp. 45–48., doi:10.1111/1467–9280.00008.

Reber,Rolf等。 “感知流利度对情感判断的影响。” 心理科学卷。 9号 1998年1月1日,第45-48页,doi:10.1111 / 1467-9280.00008。

Refsnes, Hege. “Rejecting Instructional Level Theory.” Rejecting Instructional Level Theory | Shanahan on Literacy, shanahanonliteracy.com/blog/rejecting-instructional-level-theory.

Refsnes,Hege。 “拒绝教学水平理论。” 拒绝教学水平理论| Shanahan谈扫盲 ,shanahanonliteracy.com / blog / rejecting-instructional-level-theory。

Trask, Robert Lawrence, and Robert McColl Millar. Why Do Languages Change? Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Trask,Robert Lawrence和Robert McColl Millar。 语言为什么会改变? 剑桥大学出版社,2011年。

Venezky, Richard L. The American Way of Spelling: the Structure and Origins of American English Orthography. Guilford Press, 1999.

Venezky,Richard L. 《美国拼写方式:美国英语拼写法的结构和起源》 。 吉尔福德出版社,1999年。

“What Is Leveled Reading?” Scholastic, www.scholastic.com/teachers/articles/teaching-content/what-leveled-reading/.

“什么是水平阅读?” Scholastic , www.scholastic.com / teachers / articles / teaching-content / what-leveled-reading /。

翻译自: https://uxdesign.cc/the-role-of-letterforms-in-reading-instruction-26868c1dbd01

英语 动画 教学 字母

本文来自互联网用户投稿,该文观点仅代表作者本人,不代表本站立场。本站仅提供信息存储空间服务,不拥有所有权,不承担相关法律责任。如若转载,请注明出处:http://www.mzph.cn/news/275729.shtml

如若内容造成侵权/违法违规/事实不符,请联系多彩编程网进行投诉反馈email:809451989@qq.com,一经查实,立即删除!

用法及代码示例)

)